Bitcoin’s Relevance to Ireland’s Housing Affordability Crisis

Introduction

A certain political issue in Ireland has reached fever pitch over recent years. It dominated the run up to the most recent General Election in 2020, and is now firmly back at the centre of the domestic political agenda. This issue is housing unaffordability.

Protestors are calling to “raise the roof”,[1] and it is no exaggeration to say that it has the potential to tear apart the very fabric of our social contract. Anecdotes about young people with good jobs being forced to emigrate or live with parents well into their thirties are not difficult to find. Considering the obviously stark consequences of the issue, the dominant coverage of its causes is somewhat shallow. While social policy issues such as housing are exceedingly complex, with interrelated factors that are difficult to disentangle, there is one particularly egregious factor at, or at least near, the very root of the problem that is almost entirely overlooked. That factor is a broken monetary system.

Before proceeding, it is necessary to set expectations. This article focusses generally on the fact that houses today are expensive relative to wages and seeks to expose the ‘why’. It doesn’t attempt to tackle the myriad of related issues. It is also important to note that the article endeavours to explain what is in essence a high level and largely abstract problem, which requires generalisations and oversimplifications, and is not readily amenable to concise explanations premised on simple facts. It is necessary to consider heavy and somewhat dry macroeconomic concepts such as credit cycles to properly frame the reasoning behind the hypothesis. The modest aim of the article is to persuade the reader that there is something deeper to this issue that isn’t intuitive at the outset; but is worthy of further consideration. Unfortunately, concise and compelling aren’t always compatible, so I hope you will agree that the topic is worthy of some time.

A Search for Causes

Anyone can recite that the primary reason for the housing crisis is an increasing demand for housing coupled with a shortage of supply, which means there are simply not enough available houses. This has resulted in the high prices that exclude a large portion of the population from the possibility of ever owning a home and has given birth to commonplace terms such as ‘generation rent’.

Of course, supply and demand are not themselves root causes, but are more appropriately viewed as descriptors of the issue; much like ‘a lack of money’ doesn’t explain poverty. When looking at the more illuminating causes of the housing crisis, we need to dive into why there is such a glaring mismatch between those two basic factors in the equation that generally determines price and, therefore, affordability.

There is no shortage of opinions on what these deeper causes are. Most of the academic and media discourse places blame for the problem squarely with the Government, and specifically a failing of the State to build enough houses over preceding years. Regarding proposed solutions, various commentators suggest the creation of a state construction company, greater empowerment of local councils, the liberalisation of planning laws, the modification of tax incentives, among other things. The proposals, in whatever form, are generally pathways for increasing supply, and there is little debate that this is what needs to happen to resolve the issue. The demand side of the equation is what it is; there is agreement that demand for housing has increased, largely due to demographics.

Returning to the why; the prevailing narrative is that the government left the country’s housing needs to the free market, which failed to deliver in the first instance. The consensus appears to be that the same free market certainly won’t now fix the crisis, and we desperately need the government to step in directly to resolve things.

A Question Worth Asking

It may be worth stepping back briefly and asking ourselves a very simple question. It should be undeniable that the free market, comprised of multiple economic actors interacting unfettered based on incentives and competition, can produce incredible results. While there may be no such thing as a perfectly free market in our highly regulated modern societies; for present purposes we will define it vaguely as any action taken outside the sphere of direct government intervention. Private industry delivers us breath-taking technology at affordable prices, putting supercomputers in the pockets of over six billion people. It provides us choices in clothing, entertainment and transport that makes life practically unrecognisable to those in previous generations.

The government has never had to step in to decide how Cornflakes are distributed to supermarkets, but yet, there they are, practically every time we need them. Perhaps more on point is that fact that the government has never felt the need to set up a state car-building company to ensure the average worker can afford one, notwithstanding the moving parts and complexity involved. The free market is usually highly efficient. So, why, in the year 2022, has the free market not yet delivered affordable housing?

Shouldn’t it be easier to match a reasonably-predictably growing population with places to live, than to coordinate the distribution of perishable vegetables with a shelf-life of two days across the country? Surely, our machinery, tools and products of construction today are vastly more efficient than those used in decades past, and this ought to increase output relative to cost, and therefore affordability. But alas, no. Irish housing in 2022, adjusted for the average salary, is practically at its most unaffordable level in history.[2] The data for our closest neighbour is instructive; UK average house prices are approximately sixty-five times higher than they were in 1970,[3] while the average industrial wage is approximately thirty-five times higher in the same period.[4]

Before we try to address this conundrum in earnest, is it possible that our view on the problem is somewhat warped? Is it plausible that the housing market isn’t in fact operating as an open market, and that these are essentially failings of central planning masquerading as those of the free market? Is private industry, with its greedy capitalist developers, nothing more than a politically convenient scapegoat to mask a deeper and more pernicious problem that goes to the core of our relationship with the state, and each other? What if we have misjudged the issue, and as a result, our collective urging of the Government to do more is destined to make matters worse in the long run?

This article argues that the issue at the very base of the complex pyramid of causes of housing unaffordability is a broken monetary system. This is ultimately responsible for the obvious mismatch between supply and demand, which can best be described in two related but distinct ways. First, it results in contradictory incentives that make it unlikely that we will manifest the necessary collective political will to implement the solutions that would meaningfully increase the supply of houses, no matter how clear or rational the suggestions. Second, it results in a destructive and unnatural uncoupling of supply and demand which occurs because of the evolution of property as a speculative financial asset, allowing significant mismatches to occur. The housing affordability crisis will not be sustainably cured until these upstream issues are understood and addressed.

Misaligned Incentives

There is an inherent contradiction at the very core of the housing debate that is rarely acknowledged. At a surface level, you could be forgiven for assuming that there is unanimity in our desire to see affordable housing. Nobody would proclaim to oppose its pursuit as a principal social policy objective, and a politician would do well to get elected for doing so.

This creates a perverse role play in which we must speak as if we are all aligned on the issue; however, this simply doesn’t reflect reality and so the required actions don’t follow. While it sounds relatively benign, another way to describe the concept of affordable housing is ‘falling house prices’, at least relative to incomes. Real estate generally constitutes a significant part of an Irish person’s saving mechanism, whether through a property portfolio, a future intended downsizing or ‘nest-egg’, or a pension allocation to the property market though a fund, which most people with managed pensions have. While we ‘want’ homes to be affordable, we likely don’t want the value of our pensions to diminish.

With that in mind, what proportion of Irish people actually wish to see the relative price of housing come down at all, never mind dramatically? The very moment someone gets on the ‘ladder’ their priorities flip- it is quite understandable that they would slink away from the protest and harbour a secret desire to ‘keep the roof just where it is, thanks very much’. Their next target will naturally be a lower loan-to-value and better rate on their mortgage, and plummeting house prices certainly don’t achieve that. While it might be politically correct to support affordable housing, it is simply not financially desirable for a significant portion of the population. Are we therefore confined to platitudes?

With these misaligned incentives, we are walking a fraying tightrope which represents our social contract and divides us as a nation into a modern-day version of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. Ironically, some of us may fall into both categories at once; however, it is an undesirable outcome upon any analysis. At a high level, or perhaps more appropriately at the lowest and most fundamental level, fixing these contradictory incentives is the best hope we have of resolving the crisis. It appears that if we want to untangle this Gordian knot, we have two options: either the bourgeoisie needs to stop using houses as financial assets to store value, or the proletariat need to stop using them as places to live.

Housing as a Store of Value

Why do pension funds and investors buy property? It is unlikely explained by the sheer enjoyment of being a landlord. After all, the bogeymen funds are, at least in part, investing our money so that we can afford to retire at some point in the future. Why does a pension fund representing firefighters in Berlin feel the need to buy investment property in Dublin? This is a fundamental question about the bigger picture which we seem to mostly avoid and demonstrates that it is not a problem confined to Ireland.

One of the reasons funds buy up real estate can essentially be broken down to the proposition that money no longer serves any role as a store of value. If pension funds were to hold cash, they would be out of business relatively quickly. Government bonds used to be the answer; however, interest rates have been consistently lowered over the last four decades, and in the era of low and zero rates, these bonds, which were once considered ‘risk-free return’, no longer provide sufficient interest payments for a pension portfolio to meet its obligations.[5]

At the level of the individual, the same thing applies. The concept of a viable ‘savings account’ with a bank is becoming a distant memory. Everyone gets pushed out on the ‘risk curve’ in the search for ‘yield’. In other words, people are incentivised to take risks with their money in an attempt to retain its value, which inevitably leads to speculative bubbles everywhere. While we are great at identifying such bubbles, whether in the stock market, ‘crypto’, or elsewhere, there is precious little understanding of the fact that they are fundamentally a symptom of broken money, and much more likely to occur in the absence of a prudent alternative.

When the money itself cannot be merely saved, and the once ‘risk-free’ return on money provides a negative real return, what other options do investors, large and small, have? Enter the ‘diversification’ mindset that emerges in such an environment. We have become accustomed to spreading value across various assets in the hope of keeping up with the monetary inflation rate, meaning that rate at which the money supply is increasing and debasing existing holdings. One option that has proved hugely popular has been to invest in property, which is relatively scarce. While its supply does increase, it does so at a generally slower rate than the money supply, resulting in general relative price appreciation over time.[6] This phenomenon is hardly controversial; the idea of an ‘investment property’ has entered the popular consciousness, and is something now taken as natural despite the risks, time, taxes and maintenance costs associated with owning property. It simply often beats the alternative array of melting ice cubes, and gives housing a ‘monetary premium’, increasing general prices beyond what they would and should be if based on utility value alone.

Interpretation: This chart shows the ratio between the UK House Price Index and UK Consumer Price Index (CPI). Both series have their base year (value=100) in 2015, therefore the ratio is 1 at this point.

Source: Longtermtrends.net

The Credit System

It is difficult to understand the place of property as a de facto savings account without briefly touching upon the credit system generally used to purchase it. People usually buy property with a mortgage from a bank, meaning that the up-front payment is confined to a small portion of the overall cost. This in itself is a cause of significant unfairness. Those on the ‘correct’ side of the line and able to get a mortgage to buy a house essentially reach escape velocity, whereby their mortgage payments will eventually result in full ownership of a valuable asset. Those falling short, destined to rent for life, may pay practically the same (if not more) over the lifetime of their lease, but with zero equity to show for it when all is said and done- ‘no nest egg for you.’

The creation of this arbitrary distinction, with ever-more people falling on the wrong side of it, is manifestly unfair.[7] This is so without mentioning the societal level game of musical chairs we are forced to play with home equity, in which timing and luck in the credit cycle essentially determine whether you gain the equivalent of a small lotto jackpot for no good reason or are stuck in negative equity and unable to move for over a decade. Again, we have become accustomed to accepting this utterly bizarre arrangement as somehow unremarkable.

Property has become a hyper-financialised and speculative asset and is therefore highly sensitive to prevailing credit conditions in the economy. When credit conditions are favourable, generally meaning interest rates are low,[8] finance to build and buy is more easily achieved. In the Celtic Tiger years leading to the Great Financial Crisis in 2007/8, credit was abundant, and so was building. Large numbers of houses were erected, often without need and badly planned, in an environment where the financial system was eager and willing to lend to builders and buyers alike. Property was where the party was at, and you didn’t want to miss it.

The Property Crash to the Present

Credit cycles are appropriately named, and when the inevitable hangover arrived, the music abruptly stopped. When it became clear that the credit extended could not be repaid, lending slowed. It was time to answer for the front-loading of consumption that lowering interest rates naturally causes. The demand that was pushing prices higher and higher, which was financing the materials and labour to overbuild, fell off a cliff and the entire system ground to a standstill.[9]

During the years of excess leading to the crash, demand was artificially inflated due to easy credit -people who didn’t need them and couldn’t afford them were getting mortgages because it was financially viable (or so it seemed)- and so supply surged to catch up. Suppliers were incentivised to supply, builders to build, and people to buy. When reality eventually kicked in and the bubble of artificial demand popped, the supply remained high, and we were left with badly planned ghost estates. With prices eviscerated, the incentive to build simply no longer existed as it was economically unviable to do so. Supply and demand were at a disjoint.

In the years that followed, Ireland’s growing population required a greater number of houses, which is a signal that the market would and should have picked up on if we weren’t suffering from the fallout of the ‘bust’. Without the artificially manipulated credit cycle and the financialisation of property, supply and demand would have waltzed in unison.[10] As demand rose, Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ of the economy, acting simply but efficiently through higher price signals, would have suitably prompted the market to increase supply.[11]

In reality however, the much-diminished value of property under tight credit conditions meant that nobody was incentivised to build even as demand started to swell. Bringing it to the more recent past; by the time this rising demand was reflected in the higher prices that made building economically viable, the construction industry was at a standing start. Such industries don’t scale up and down overnight, and when it became profitable to build again, supply was always going to be caught entirely off guard and lag significantly. We are now in a period in which supply is trying to scale up to meet demand, constrained both by physical real-world limitations and increasingly badly aligned incentives thrown on top for good measure.

None of this is simple, and if the above section wasn’t particularly clear to you, the takeaway is as follows: all else being equal, more demand for housing is naturally reflected in higher prices, which incentives building, which in turn increases supply, which in turn lowers prices; and this happens iteratively and constantly until an equilibrium is reached. This is how the market should work, at least in theory, and the fact that it hasn’t happened with housing in recent years clearly demonstrates something is deeply and systemically wrong.

Solution Whackamole

Many of the remedies being proposed are merely proposals to paper over cracks that have a more fundamental cause. Rent controls and vacancy taxes may indeed improve the situation in the short term for a certain cohort; however, they do not fix the root problem, and in the absence of more permanent solutions, such measures may actually backfire.

Taking the example of rent controls; it can be logically extrapolated that if rents cannot be raised on existing tenants, this is likely to be priced in prematurely to new tenancies, which will hurt those most in need of shelter. Further, the existence of such rent pressure zones, which were introduced in 2016, also logically disincentivise building and investment in the areas in question, suppressing the natural price signal which should be translated into the supply needed to bring down prices sustainably. We are swapping a current problem for a future larger one.

Everything we do in the absence of systemic change results in a contradiction. The mortgage lending rules, which were very recently increased, were introduced in 2015 after the crash to curb the excessive credit growth that was pushing up property prices.[12] The flip side of this, is that building in Ireland became relatively less financially competitive than in countries with looser lending arrangements. After all, the market for building materials is generally global, so introducing such rules also hinders supply, leading to eventual higher prices in any event. It also means that the international funds competing with Irish buyers are at a distinct advantage.

A Broken Monetary System

‘A broken monetary system’ may sound vague and elusive. What does it mean? While this article isn’t a call for a return to the Gold Standard, it can best be highlighted by briefly explaining how the monetary system used to operate. Until 1971, the currency we used was essentially an IOU redeemable for Gold. Gold’s scarcity, and the currency’s peg to it, meant that one could save in the money itself. There was no need to monetise other assets needed to live, such as houses, to preserve purchasing power. Institutional and individual savers alike could simply hold the money, which was a claim to the Gold.

The money we use is merely an accounting system and means to transfer value efficiently across time and space. When the accounting system fails to transfer value through time, this causes significant negative externalities. It is a natural and understandable human desire to maintain wealth. If our accounting system fulfilled this function as it used to, people would merely hoard claims on the abstract accounting system, harming nobody, rather than hoarding things others need to live. The consequences of it not doing so manifest in what we are currently witnessing, and this is not confined to housing.

The last 50 plus years of economic history, with free-floating fiat currencies that are unpegged to anything and lack any enforceable scarcity, have led to the increasingly desperate financialisation of other things. Interest rates have been lowered, and national debts mounting, since the 1980’s. As debt burdens climb, lower interest rates allow governments to borrow more and more in order to service past debt, without the interest due on the debt becoming too great. The supply of money has been increased in various ways, including through the lending mentioned earlier; however, another pertinent method worth outlining is the purchasing of government debt by central banks over recent years.

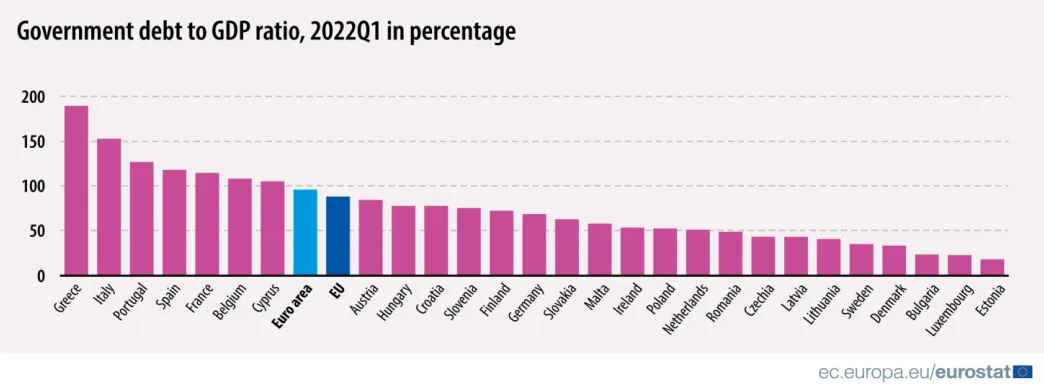

The precise mechanics of this can be obscure; however, suffice it to say that ‘we’ are now firmly in the habit of creating money out of thin air to buy our own debt back through government bonds. It is by bidding for national bonds in such a way that the ECB keeps interest rates in the Eurozone artificially low- in other words, below what the market rate would be if only other free market participants were purchasing them. If they didn’t do this, countries such as Italy and Greece, with national debt to GDP ratios at 134% and 193% respectively, would enter a debt servicing spiral that would end in inescapable bankruptcy. We have demonstrated incredible cognitive dissonance in hoping beyond hope that this wouldn’t have the effect that would seem logical- a loss of purchasing power through the debasement of the money, which has now shown up through price inflation. This artificial manipulation of interest rates by creating money at the stroke of a key has allowed us to avoid the economic reality of our countries’ balance sheets for quite some time and has been responsible for the unnatural credit cycles described above.

It is a fact that national debts in the entire developed world have been increasing significantly for decades. The average Eurozone debt-to-GDP ratio is now precariously close to 100%. Worthy of a book in itself, it is abundantly clear that this evidences a short-termism and willingness to kick the can down the road upon future generations. Nation States are not fiscally prudent given a long view, and when we consider the four-year election cycle, this should come as no surprise. There is a point at which debt burdens become too great, and when escaping a debt spiral becomes a practical mathematical impossibility.

The consistent trend of lower interest rates and higher debt demonstrates irrefutably that countries tend to overspend. A nation (or group of nations such as the EU) that can print its own currency will never default on its debt in nominal terms; however, at a certain point the only realistic option for deleveraging the debt that is available is the devaluation of the currency.[13] Such a devaluation of the currency results in a form of financial repression, whereby savers and those that have extended credit are forced to take a loss in purchasing power. This is the mechanism through which we pay for lunches previously eaten and is how we get collectively poorer.

“It may sometimes be expedient for a man to heat the stove with his furniture. But he should not delude himself by believing that he has discovered a wonderful new method of heating his premises”– Ludwig von Mises.

The Failings of Politics

The cause of this overspend can be viewed as a form of populism. Perhaps not the egregious sort with which we usually associate the phrase; however, a government promising to do a little more will always have an edge over one talking about balancing books for the long-term financial health of the country. It is simply the systemic path of least resistance. Democracy’s in-built tendency to cause or allow monetary inflation is a phenomenon that has been generally masked in recent decades by factors such as technological progress, demographics, and globalisation, which means that even as the money supply expanded, prices generally did not. It appears this period may be at an end.

If this natural tendency to debase the money is caused by governments trying to appease their populations; there is a logical case to be made that this has led to the monetisation of housing described above. After all, those with wealth are going to act rationally to preserve it. If so, isn’t demanding ever-more of the government potentially bothersome? While we obviously need to bail the water out of the boat, there is no point in doing so if we aren’t paying enough attention to the horizon to ensure we aren’t cruising directly for more icebergs.

It is known that if a frog is placed in water that is gradually brought to a boil, it won’t notice the temperature change until it is too late. If we swap ourselves with the unfortunate frog, perhaps one of the signs that the water is coming to a boil is staring us directly in the face. Thinking more deeply about what it would look like, if it did look like our national debts were too great, our governments too large, and our spending too frivolous could be an important exercise to undertake in the name of responsibly scanning the horizon.

Conclusion

Housing affordability is an exceedingly complex policy issue and trying to reduce its underlying causes may be a fool’s errand. That said, it is notable that it appears to be a major issue across much of the developed world, and not unique to Ireland.[14] While there are outliers, it seems like too much of a coincidence to conclude that the issue can be fairly attributed to specific market interventions or lack thereof by governments around the world in the sphere of housing policy, or indeed local market conditions. Factors common to practically all governments in the developed world are ever-increasing money supplies, lower interest rates, and higher debt to GDP ratios.

If this article could be packaged into a conclusion, it would be that the housing affordability crisis has one clear underlying cause, which manifests itself in two clear ways. The underlying cause itself is broken money, meaning that money that is manipulated by governments and central banks does not hold its value over time, which in turn leads to the use of other assets, such as housing, as substitute stores of value to negative effect. The first manifestation of this is the creation of perverse incentives that make it difficult to achieve the consensus required to solve the problem. The second is the creation of artificial credit cycles, which lead to a catastrophic decoupling of the natural equilibrium between supply and demand, which would otherwise be more accurately guided by price signals in the market.

In the short term, we clearly need to do whatever is necessary to increase supply, which are many of the things repeated ad nauseum in the academic commentary; however, with an understanding that if we don’t mend the fundamental link between supply and demand, this issue, and others like it, will persist. We shouldn’t be naïve in thinking that affordable housing is in everyone’s interest, even if it is quite clearly in the collective interest. Many of the proposals for increasing the supply, such as greater zoning of residential land, will be strongly resisted by those with an understandably vested interest in maintaining the status quo. Until we remove the direct confrontation in the incentives at play, progress will be very hard won.

If we don’t grasp and endeavour to solve the issue at the base layer, which is the abstract mechanism of economic coordination -the money- then housing in Ireland will most likely remain a mess and a hugely divisive political issue into the future. There is no quick fix, but we need to get to work on the long fix. How this is potentially achieved is another article entirely; however, for now, it seems clear that a bigger government and more of the reckless spending that heralded our arrival to these shores is not the answer.

Posted originally on https://richmoney.substack.com/

[1] https://www.raisetheroof.ie/

[2] Housing affordability itself can be measured in different ways, and differs in various regions: https://www.housingagency.ie/data-hub/house-price-income-ratio What is clear, is that the trend of housing affordability has been getting generally worse since the 1970s: https://assets.gov.ie/205477/d744837d-8f03-4ff0-82dd-4763df823c95.pdf

[4] https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/nominal-wages-consumer-prices-and-real-wages-in-the-uk-since-1750

[5] Ironically, this lack of ‘yield’ has also pushed pension funds into risky leveraged investments, such as the ‘Liability Driven Investments’, which recently almost wiped-out pension funds in the UK. The dynamic is not dissimilar to that of the ‘Collatoralised Debt Obligations’ that you may be familiar with from the housing crash, though with government debt replacing bundled mortgages.

[6] https://data.gov.ie/dataset/price-of-new-property-by-area-by-year

[8] Though not exclusively. After the property crash in 2008, interest rates remained low; however, credit was not easily available due to increased scrutiny and tighter borrowing limits, etc.

[9] This is clearly an over simplistic take on the causes of the previous property bubble and subsequent crash; however, it is, I believe, a useful summary. This period is described in detail in this European Commission paper: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/economy-finance/eb061_en.pdf

[10] This may appear to be a utopian view on supply and demand, which of course don’t always result in a perfect equilibrium; however, the argument is that the equilibrium would have been better achieved in a properly functioning monetary system.

[11] A fun fact and aside- Smith only used this term once in his text the Wealth of Nations, and it didn’t even have the meaning ascribed to it above, which evolved some time later.

[12] The Irish Central Bank was attempting to counteract the credit conditions created by the policies of the European Central Bank. For a consideration of this see: https://mises.org/wire/ireland-when-mmt-and-price-controls-collide-little-remains

[13] The other option is for countries to default on their debt outright. This would cause a severe breakdown of the economy and a deflationary spiral, as trust evaporates. An outright default is unlikely to be the chosen option when debasement is the opaquer alternative.

[14] https://www.worldfinance.com/infrastructure-investment/solving-the-global-housing-crisis